How to Overcome “Analysis Paralysis”

“If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice”

- Neil Peart, Canadian lyricist and drummer

We’ve been successfully developing and launching new products for decades. A problem we see all too often is teams not finding the right balance between information-gathering and decision-making.

Some teams take unwarranted leaps with nowhere near enough relevant information, driven by real or imagined deadlines, thus inadvertently taking on huge risks.

Other teams become “stuck” – unable to make progress because they are (rightly) motivated to be very rigorous, but lose track of their schedule obligations; this is “analysis paralysis”, which also puts projects at risk.

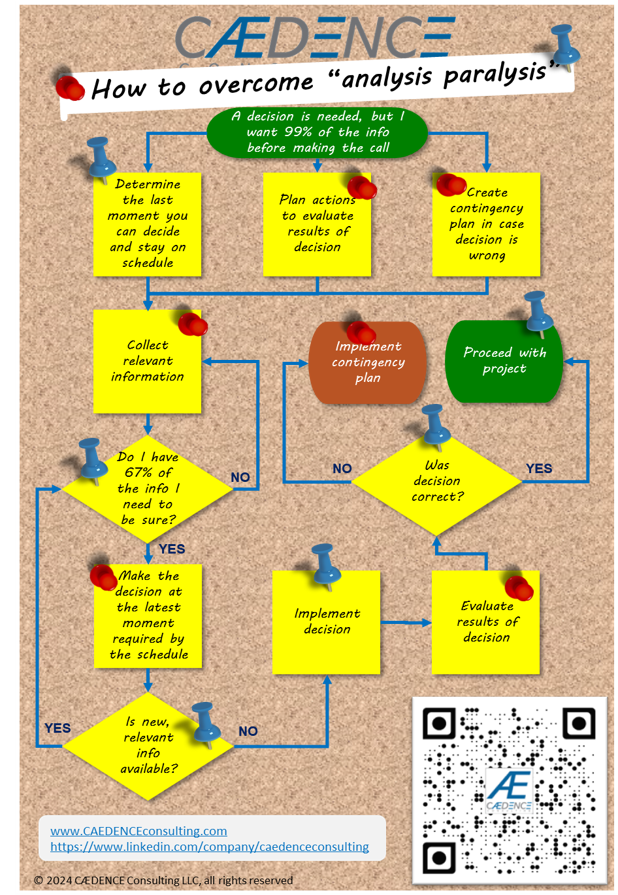

We’ve developed the heuristic shown in this infographic based on our experience in automotive, aerospace, heavy vehicle, semiconductor, electronics, and other industries to help teams find the right balance between schedule pressure and rigor.

The key things to remember are:

• "Fail fast“: The wrong decision will drive learning, but you will learn nothing while waiting.

• Waiting for all the info necessary to be sure of a decision can create a bigger problem than just making a judgment, learning from mistakes, and then making adjustments as-needed.

• 60-70% of the desired info is usually enough to make a judgement and proceed. The bigger (more irreversible) the consequences of the decision, the more info you’ll want.

• Do not waste time re-visiting a decision unless new, relevant information becomes available.

• Verify: pay close attention to the results of the decision and adjust course if necessary.

Over the years we’ve been exposed to Six Sigma, Juran, Deming PDCA, 8D, Dale Carnegie, A3, Shainin, and more. Each technique works pretty well, and has been demonstrated many times in a wide variety of industries and circumstances. At the core they are all essentially the same!

Each approach relies on an underlying logical flow that goes like this: [a] make sure the problem is clearly defined; [b] be open to all sources of information; [c] vet the information for relevance and accuracy; [d] use the process of elimination to narrow down all possible causes to the most likely few; [e] prove which of the suspects is really the cause of the issue; [f] generate a number of potential solutions; [g] evaluate the effectiveness, feasibility and risk of the potential solutions; [h] implement the winning solution(s); and [i] take steps to make sure your solution(s) don’t unravel in the future.

The differences between the paradigms resides in supplementary steps and toolkits. For example, 8D contains the important “In