How can I impact product quality when I'm not the one building the product?

How can I impact product quality when I'm not the one building the product? Your decisions and actions as managers and engineers have a huge impact on quality!

“Quality does not happen by accident.”

- Joseph Juran, Romanian-American management consultant and engineer

Operations Manager: "We've had a lot of scrap on the production line this month." Engineer: "Well, the operators keep making mistakes." If this bit of dialogue sounds familiar, read on.

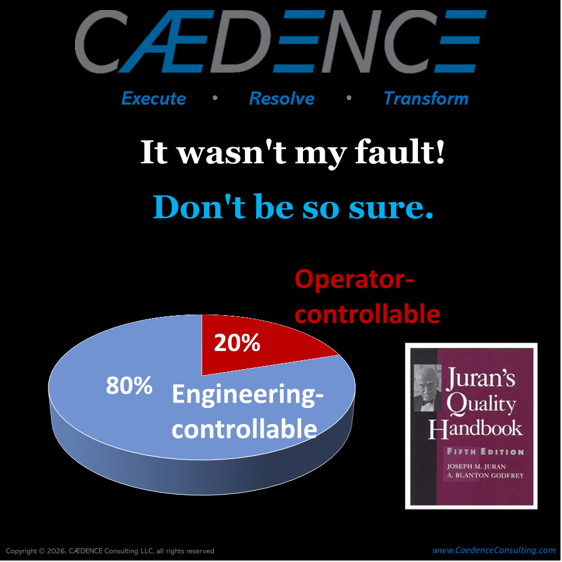

Joseph Juran analyzed numerous studies across many industries. He found errors were:

- operator-controllable: 20%

- engineering*-controllable: 80%

*Juran actually wrote "management" rather than "engineering", but I've always found that wording just gives the engineers another way to duck accountability. They can't blame the operators for issues anymore, but now they can blame management. And, for sure, management plays an absolutely essential role. But for the purposes of this post, we're going to focus on the example of a physical production process, where the process, manufacturing, and design engineers have an outsized influence on how the operation runs.

The late Joseph Juran remains an icon in quality circles, and for good reason. His philosophy (that quality should be managed as an integral part of business strategy involving all levels of leadership) was massively influential in establishing Japanese electronics and automotive dominance in the 1970's-1990's. His teachings were subsequently adopted by companies everywhere. (I first encountered them at Texas Instruments in the mid-90's). And they remain highly relevant to this day.

Juran realized that all defects can be classified as "operator-controllable" or “engineering (management)-controllable".

Defects are "operator-controllable" if operators have the following 3 things:

- A way of knowing exactly what is expected of them e.g., clear process specifications and visual aids, comprehensive training, etc.

- A way to know their actual performance against the expectation e.g. visual inspection or measurements by themselves, or by others communicated to them, etc.

- A way to adjust what they are doing if it is not meeting the expectation e.g. knobs on a machine, pressing harder on an assembly, etc.

Only if all 3 conditions are met with no exceptions do operators have everything they need to do good work. If defects occur anyway, they are classified as "operator-controllable".

If any of the above criteria have not been met, it is because the engineering (management) job is not complete. In that case, resulting defects are classified as “engineering controllable".

“Engineering" includes all functions who are not touch-labor: process engineers, design engineers, project managers, technicians, quality assurance, line supervisors, managers, etc.

If you extend the thinking beyond hands-on manufacturing to include business processes, product development, supplier management, and other practices within a business, you can see why Juran chose the word "management". If errors are occurring in ANY type of process, look first to the designer of the process, not to the person executing the process.

More about Juran:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_M._Juran

Over the years we’ve been exposed to Six Sigma, Juran, Deming PDCA, 8D, Dale Carnegie, A3, Shainin, and more. Each technique works pretty well, and has been demonstrated many times in a wide variety of industries and circumstances. At the core they are all essentially the same!

Each approach relies on an underlying logical flow that goes like this: [a] make sure the problem is clearly defined; [b] be open to all sources of information; [c] vet the information for relevance and accuracy; [d] use the process of elimination to narrow down all possible causes to the most likely few; [e] prove which of the suspects is really the cause of the issue; [f] generate a number of potential solutions; [g] evaluate the effectiveness, feasibility and risk of the potential solutions; [h] implement the winning solution(s); and [i] take steps to make sure your solution(s) don’t unravel in the future.

The differences between the paradigms resides in supplementary steps and toolkits. For example, 8D contains the important “In